At Academy Bay diving we get many enquiries about what can be expected from scuba diving in the Galapagos Islands. The wildlife is rarely doubted due to the plethora we have here but what are the water conditions, are there currents and, how warm, or not, is the water?

Here we have two main seasons and that affects the water too. Right now we are in the cooler season, both on land and in the water.

The uniqueness of life on the Galapagos Islands is well documented and, for nature lovers, a visit to the region can be an inspiring and life-changing experience. For those visiting the Galapagos and coming to dive, understanding the reasons behind its extreme diversity can contribute to a deeper appreciation of this incredible part of the world.

A Phenomenon of Nature

There’s one natural phenomenon that can take the major credit for the abundance and diversity of both the marine and terrestrial wildlife of the archipelago. The chilly Humboldt Current originates in the

Antarctic, driven by strong winds to flow up the west coast of South America and push the cool waters on a path straight through the Galapagos Islands. It brings with it nutrients that it gathers from the dead and decaying matter on the sea bed, and when it mixes with the warmer South Equatorial Current, these nutrients rise from the deep to sustain the plankton that forms the basis of the islands’ food chain.

Antarctic, driven by strong winds to flow up the west coast of South America and push the cool waters on a path straight through the Galapagos Islands. It brings with it nutrients that it gathers from the dead and decaying matter on the sea bed, and when it mixes with the warmer South Equatorial Current, these nutrients rise from the deep to sustain the plankton that forms the basis of the islands’ food chain.

The current affects every aspect of life, both on land and in the surrounding oceans.

The Water Temperature: Some people who visit the Galapagos Islands are taken aback by the chilly temperatures of the water, due to the presence of the Humboldt Current. June to December is when the oceans are at their coldest, as these months are marked by an increase in the current. From November to May, the current is still present, but is significantly weaker, allowing warmer waters to reach the islands.

The Weather Patterns: The current is also responsible for the two distinct seasons that are experienced on the archipelago: the cool, dry season and the hotter wet season. In the dry months (from June to October), powerful trade winds cause the current to pick up. Since the waters surrounding the islands are cooler, there is less evaporation, and therefore fewer rain clouds form. While a Galapagos wildlife cruise can be enjoyed at any time of the year, the two seasons can offer quite different experiences.

The Wildlife: Even beyond this remote archipelago, the presence of the Humboldt can be felt and it is credited as the “most productive marine eco-system in the world” – responsible for an astounding 20% of the entire world’s marine catch. Every single species – reptile, mammal, bird, invertebrate or marine – on every single island, including the surrounding waters, is affected by and dependent on this powerful current. The nutrient-rich waters it brings directly or indirectly provide the food sources that sustain the huge wildlife population.

The El Niño Effect

The effect of the current can perhaps most clearly be seen in its absence. During the weather phenomenon known as El Niño, it is weakened by warmer winds and a decrease in air pressure. During these times, which occur cyclically every two to seven years, there is a marked reduction in breeding activity of the local wildlife. There are far fewer fish, and therefore a massive decline in the food sources of the islands, resulting in great numbers of animals starving to death.

The complex and definitive role this cold ocean current plays in sustaining the rich biodiversity of the islands is yet another fascinating aspect of one of the most intriguing places on the planet.

Scuba Dive with Gentle Giants

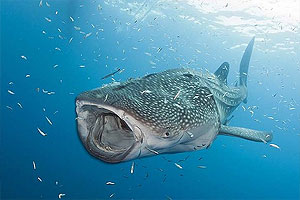

With the cooler waters comes Whale Sharks. What scuba diver doesn’t want to swim alongside these gentle giants!

Of the 32 shark species of Galapagos, the massive Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus) is by far the largest. These are, in fact, the largest living fish in the world. While they’re found in the majority of the planet’s warm and tropical oceans, the Galapagos Marine Reserve – which encompasses the waters surrounding this unique archipelago – can boast an interesting phenomenon as the region is particularly attractive to pregnant females of the species.

Physical Characteristics

The clue is in the name (although they are most definitely not whales) and these huge sharks can grow up to 18 metres long – to put that in context, it’s bigger than the largest passenger bus. While individuals of that size are not uncommon, the average is a still-mammoth 12 metres long.

The shark’s mouth is a gigantic portal, which can be up to 1.5 metres in width and is positioned at the very front of its head. The head itself is flat and wide, with a rounded snout and disproportionately small eyes. They have more than 300 teeth, although they appear to serve little or no purpose, as the species is a “filter feeder”.

The body is generally greyish-blue in colour, with the presence of highly distinct uneven blotches of yellow distributed over the back and sides. The sharks have two large dorsal fins, two pectoral fins and an upper and lower fin on the tail.

Feeding

There are five massive gill slits on either side of the head. The shark feeds by taking in huge amounts of water and plankton through its mouth at high speed, then effectively sieving it through its gills – hence the term “filter feeder”. The sieve system is made up of tough cartilage and filter pads containing tiny pores, which ensnares the plankton particles but allows the water to pass through.

Behaviour

The species is extremely migratory and have been recorded travelling thousands of miles each year, returning to the same place to feed and give birth. While many of the shark species of Galapagos are seen in great numbers in the waters around Darwin and Wolf Islands, curiously the vast number of Whale Sharks that congregate are pregnant females. This is the only part of the world where this happens and scientists have no concrete evidence as to why it is so.

Growing the Knowledge

Incredibly, there is very little research-based information on the breeding habits of the species. Until now there has only ever been one analysis of a pregnant female, which was found to be carrying over 300 pups in varying stages of growth. It’s not known definitively how long the gestation period is, how often they give birth, or even where breeding takes place.

Since 2011, the Galapagos Whale Shark Project (GWSP) has been working to rectify this gap in knowledge, in order to solidify conservation efforts and increase their understanding of the species. The team is using tagging and ultrasound technology to track the migration to and from the archipelago and learn more about the animal’s physiology.

Photo taken by Jonathan Green

Conservation

GWSP is also doing valuable work in the conservation of this magnificent shark species of Galapagos, through education programmes and initiatives. With threats coming from illegal fishing (to satisfy the demand for their fins in the Asian market) and a decline in food sources, it’s vital that the profile of this strangely beautiful ocean giant is raised, in order to secure its survival.

Written by: Charli Pocock